I repeatedly read the other day an interview by Deutsche Welle with professor Herbert Brucker, researcher on international migration and European integration with the Federal Institute for Employment Research in Nurenberg. He basically argues in favor of immigration to Germany, putting the number of needed immigrants at 400.000 a year. According to his estimations, in 20 years one third of the German population will be of foreign origin from 25% today. During the same 20 years, the big cities will see their percentage of immigrants reach 70%. By foreign origin he means immigrants or people with non-German parents or grandparents.

He essentially brings two arguments for such an ample demographic change, which I believe to be questionable and contradicted by facts.

The first argument is that accepting such a large number of immigrants is necessary to keep the economy competitive against negative demographic trends.

A first question would be: what do we understand by and how do we measure the competitiveness of the German economy to reach that conclusion? I turned to the World Economic Forum which ranks competitiveness worldwide based on its competitiveness index. And the picture that it paints is relevant, I think, to our discussion.

Singapore ranks first after trading places with the US which is now second. Germany is seventh after Japan. It should be noted that the two countries stay grouped together when it comes to oldest populations also, coming second and third. Despite this problem, their strategies to maintain competitiveness have been worlds apart as far as immigration is concerned. Japan has almost always had a virtually non-existent immigration flow as it did not consider immigrants a pre-requisite for competitiveness. However, it has been investing in technology. It recently started marketing robots that take care of the elderly. And so we get to the crux of the matter.

Singapore ranks first after trading places with the US which is now second. Germany is seventh after Japan. It should be noted that the two countries stay grouped together when it comes to oldest populations also, coming second and third. Despite this problem, their strategies to maintain competitiveness have been worlds apart as far as immigration is concerned. Japan has almost always had a virtually non-existent immigration flow as it did not consider immigrants a pre-requisite for competitiveness. However, it has been investing in technology. It recently started marketing robots that take care of the elderly. And so we get to the crux of the matter.

Financial Times noticed in one of its articles halfway through the year the lack of ambition and complacency that engulfed the German industry. It may stay competitive, and yet it is about to “miss the boat” due to lack of investments. Indeed, labor productivity growth is slower than before the crisis, and the value of capital stock per worker is close to 2002 levels. Therefore, I would conclude that profit margins seemed to have been initially based on a large and cheap labor force, probably imported and less on shareholders risking their capital.

For those who doubt that pressure to keep up competitiveness was first and foremost on the labor market, here are two relevant statistics. Bloomberg mentions that two researchers with the Institute for Economic Studies in Berlin noticed that in 2017 featuring full employment, 25% of the German wages were low (less than two-thirds of the median wage), a significantly higher percentage than the OECD average of 18.9%. A share that has remained relatively unchanged since 2008!

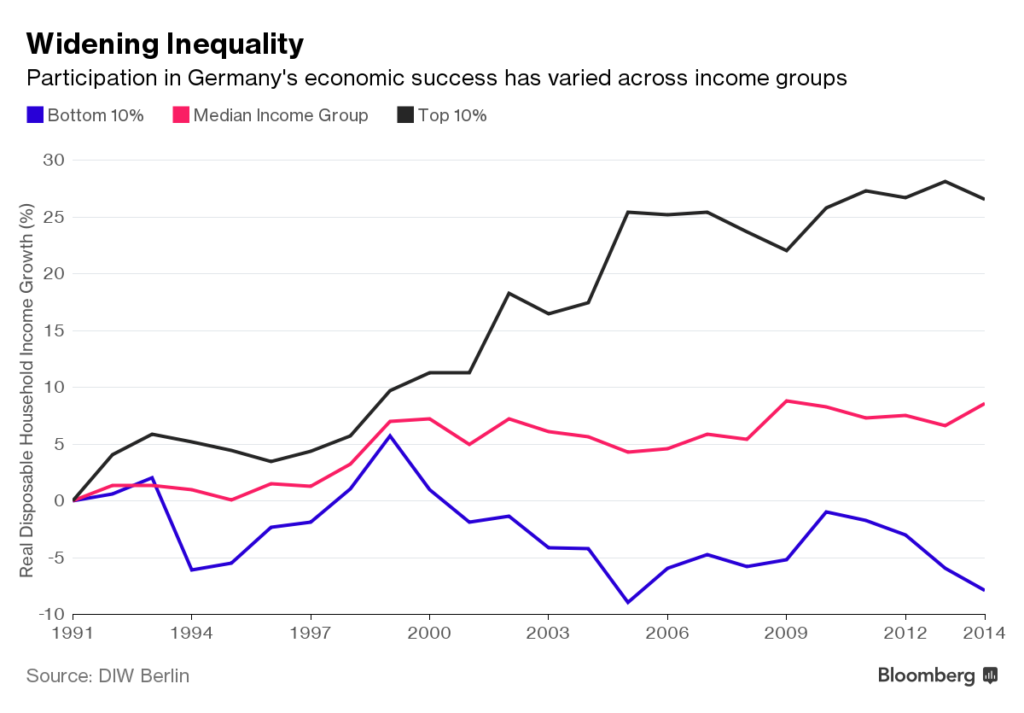

Here is the explanation, if you are looking for one. According to the same study, 30% of lowest-paying jobs are held by immigrants or their children, with 30% of them in Eastern states. Labor force pressure leads to wealth gaps and a rising polarisation detrimental to the middle class, as the graph below demonstrates.

Under these conditions, advocating immigration as a means to keep German competitiveness could more directly translate to downward pressure on German wages to offset the lack of investment by capital holders.

The implication here is that Germany will lag behind in innovation. OECD notes that the sectors which saw the fastest-growing number of patents, such as IT security or semiconductors, are dominated by the US, China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan.

The second questionable assertion by professor Brucker is that „According to research conducted in the area, contact between German and foreign-born populations is quite intense, and social integration works surprisingly well. We only need to get used to the idea that the big cities will no longer have an ethnically homogeneous population.” And yet … The rise of the far right to become the third most popular party in Germany seems to show a different reality.

Prof. Dan Dungaciu rightfully said in a discussion I posted on the blog that „it is not so dramatic when a far-right party gets 13% in France, in Denmark, in Holland. But when it happens in Germany, a red line has been crossed, an essential postwar consensus. The “right of the far-right” has risen that horrified so many Germans. The emergence of a far-right party ended the German consensus. We cannot yet tell what the psychological impact of this rise will be and how it will increase other crises in Germany: retirement crisis, army, security crises, etc.”

And the Alternative for Germany manifesto has been anti-immigration, Eurosceptic and nationalist which seems to rather reflect Germans` frustration with the loose immigration policy of their political leaders.

That loose policy and the public statements that endorse foreign labor will, note well, encourage immigrants from all corners of the earth to come in droves in a much less selective way than the professor suggests. It is playing with the fire that Ms. Merkel lit and now finds very hard to put out. She just managed to have it smoulder courtesy to well-paid Turkey.

Under these conditions, maintaining German competitiveness by putting the pedal to the metal on immigration and ignoring what the digital transformation has to offer can only embolden extremist political groups.

German economic and political elites must come down from their ivory tower and make sure that Germany is not turned into a Tower of Babel by their complacency and greed. With all the “success” that the Tower had …

Have a nice weekend!