The Finance Ministry thanked the Central Bank for its policy to devalue the RON, the national currency. “The Central Bank, as an independent institution sets its own policies, but a weaker RON will definitely have a positive impact on our country’s exports” stated the Finance Ministry official.

What impression would this statement leave on you? It would be equal to a shock wave through the economy, a paradigm shift which would propel Romania into a “film” completely different from the one it has been playing in these past decades when exchange rate stability has been fiercely guarded. It might be like something from a sci-fi film for us, but in Poland’s case, it is as real as it gets. The thanks were extended by the deputy Finance Minister to the Polish Central Bank.

Citibank estimates that last month the Polish Central Bank bought foreign currency on the local market worth around $7 billion in an attempt to weaken the zloty and increase the competitiveness of Polish exports. Can Poland be suspected of competitive devaluation and if so, the question this raises for us is: What are we waiting for? Stand by as our exports lose their competitiveness?

Well, we are waiting for budgetary and macroeconomic policies as reasonable and predictable as Poland’s. (Alas, we wished to copy the Polish model only when the dismantling of the private pension system was concerned, a measure that Polish politicians are regretting and are trying to fix.)

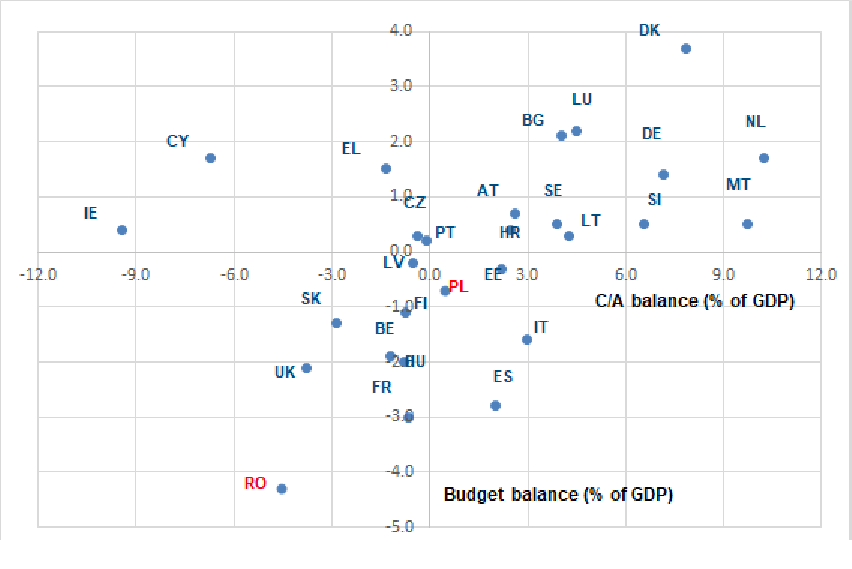

As a picture is worth a thousand words, please see the graph obtained from our colleagues in the BCR’s Research Department. It shows where Romania stood in terms of budget deficit (vertical axis) and current account deficit (horizontal axis) in relation to other EU countries at the end of 2019 before the pandemic-induced crisis.

Romania was an ‘outlier’, exhibiting completely different circumstances from the rest and mainly from its fellow Central and Eastern European states. It featured large deficits unnecessarily generated in times of economic boom. Instead of keeping our ‘bullets’ for rainier days, we gloated over the miracles that public sector wage rises would produce. That helps explain how the weak economic state in which the crisis found us (again!) did much to restrict the moves to cushion the crisis.

Basically, given what has happened in the past 12 months, the local exchange rate, unlike the one in Poland, became hostage to how the public deficit is funded. When 50% of the public debt is denominated in foreign currency, then any RON devaluation will lead to a significant increase in budgetary expenditure. And that is not acceptable.

Poland is not in the same predicament as its reliance on external funding has been declining mainly since 2016. This was made possible by a prudent budgetary policy which resulted in a budget deficit constantly far below Romania’s. In 2018 and 2019 it was close to zero, whereas in Romania is reached 3% and over 4 %, respectively. At the same time, the Polish government bonds were propped up by central bank purchases whose goal was to lower the government’s financing costs and its reliance on external financing.

Why hasn’t the National Bank of Romania acted along the same lines? It was because of the country’s unique budgetary policy which has caused it to spend most of its tax revenue and social contributions on paying pensions and public sector wages. Therefore, the money the NBR would have printed would have gone to pensions and wages and not towards development and investments. The general elections at the end of 2020 created a setting that was not favorable to budgetary corrections, however necessary they may be. The proof lies in the unseemly debate on raising pensions by 40% as the budget is bursting at the seams and the rating agencies had their finger on the downgrading sovereign credit rating button.

All that was left to do under these circumstances was to celebrate with fireworks foreigners’ willingness to credit our economy and ignore the massive dependence on a stable exchange rate the external funding brings about.

Meanwhile, the competitive devaluation strategy for the Polish zloty and the announcement that it should continue shed new light on NBR’s recent decision to lower the key interest rate. Even though a significant devaluation of the RON by purchasing foreign currency is out of the question, a gradual and limited devaluation by lowering interest rates would be much better tolerated by the economy. (and by the local psyche which differs radically from the Poles’, much less fixated on the exchange rate.)

In conclusion, we may see at some point our own Finance Minister thanking the NBR. Not for devaluing the RON, but for keeping its stable.

Not even after 30 years have passed since the iron curtain fell, have the macroeconomic paths of Romania and Poland converged.