In a discussion I had before the Emergency Ordinance (EM) issued by the Romania Government bringing a whole host of new taxes and duties was voted in, an important person was telling me that: “To assume that a political decision will be overturned based on technical grounds is unconceivable. This has never happened before”. Here is the problem. The economy works on economic laws whose rules do not care much about politics, but rather about the principles of demand and supply, return on capital, return on investment and other such “trivia”. The sharp drop of the local stock market have more than proved that.

Now that the emergency ordinance with major tax effects has been issued, the companies concerned can only revisit their business plans, strategies and even whether their presence in Romania makes sense any more, while trying to explain once more what for well-informed professionals stands to reason. Given the circumstances, I also suggest to take a dispassionate look at how the behavior of banks and private pension managing companies is expected to change based on absolutely reasonable business decisions.

Now that the emergency ordinance with major tax effects has been issued, the companies concerned can only revisit their business plans, strategies and even whether their presence in Romania makes sense any more, while trying to explain once more what for well-informed professionals stands to reason. Given the circumstances, I also suggest to take a dispassionate look at how the behavior of banks and private pension managing companies is expected to change based on absolutely reasonable business decisions.

Les us start with the banks. Not the retail banks, but the central bank, the NBR [National Bank of Romania]. The setting by the government of a ROBOR rate at 2%, seen as “normal”, is a serious interference in the NBR`s monetary policy, in theory established at arm`s length. Faced with rising inflation, the textbook, logical reaction of the NBR is to increase the benchmark interest rate, all the more so since it is currently below the inflation rate, therefore, real negative.

The step, however, will prompt ROBID interbank interest rates (interest rate banks charge each other for deposits) and ROBOR rates (interest rate banks charge each other for loans) to readjust. The rule of the game is to have both of them set around the benchmark interest rate, with the latter somewhere in the middle. The problem is that under the EM as the ROBOR rate increases with the benchmark interest rate, the higher tax rate will substantially decrease retail banks profitability. In other words, the NBR`s monetary policy decisions will lead to profitability falling across the banking system and ultimately, to the shutdown of some banks. How independently and effectively will the NBR monetary policy fight against inflation, knowing that as central bank it will have a hand in weakening the system whose stability it is called to oversee?

A remark has to be made here. What happens now is also the result of the “unorthodox” approaches which the NBR took pride in on occasion. For years, the ROBOR rate was purposely decoupled by the National Bank from the benchmark interest rate. Both ROBID and ROBOR rates were for a long time much lower than the benchmark rate which made the latter merely symbolic. The outrage this year over the high ROBOR rate, and also the EM decision show, in my view, that politicians considered this abnormal state of affairs as normal. Decoupling interbank interest rates from the benchmark interest rate and creating unrealistic expectations around them is a NBR decision which we see taking its toll today.

As for the retail banks, let us notice something that actually stands as the conclusion of what has been explained so far. The charge that retail banks will have to pay is an inflation charge, the latter being the product of the government`s economic policies. The explanation lies with the fact, that as inflation rises, interest rates should follow suit and depart from the 2% rate arbitrarily set by the EM. And thus the taxes paid by banks will increase.

Will there be inflationary pressures? As we well know, they already exist. Moreover, if we look at similar tax measures taken in countries such as Hungary and Poland, most corporate tax hikes increased prices in 1 to 2 years, which translated into higher inflation.

As far as banks` changes in strategy go, it is not hard to foresee their consequences. The catchphrase is to be expected: mitigate the impact on profitability. This objective will firstly be met by managing costs. In our case, the focus will first go on the asset tax itself. To lower it will require reducing the reporting base, the value of assets, respectively. My expectation is that banks will look into available methods that help lower the number of assets on their balance sheet.

They will therefore, be less keen on drawing in savings from individuals, given in particular that the value of deposits is considerably higher than that of loans. Under these circumstances we can expect to see interest rates on deposits meant to draw in savings decrease, which means that rising inflation will erode even further the real value of individual savings. This could prompt more and more Romanians to keep their money “under the mattress”.

With regards to bank assets, I expect that a first analysis will focus on owned government bonds, as retail banks in Romania have the largest exposures in Europe to this type of securities. Cutting the exposure is a fast way to reduce the asset value, the consequences being borne, however, by the public budget. Lower bank exposure to securities meant to finance the budget will have the budget rely more on external funding and also expose the foreign exchange market to volatile foreign investor sentiments. Moreover, lower demand will push the interest rates paid by the government up.

At the same time, banks will re-examine operating costs and costs relating to distribution channel profitability under the new tougher requirements, set by the asset charge. This means that distribution channels will be cut back which will result in lower access to banking services. In the meantime, the profitability of banking products will also come under scrutiny based on the new conditions, which means that some categories of clients and products will be screened out. Overall, the level of financial intermediation (assets/GDP) is likely to stagnate or fall even further below the regional, not to mention the EU average, making access to funding for the economy and individuals harder. I expect this to spill over into the overall economic growth which will take the final hit, with the property market, the main beneficiary of mortgage loans, being particularly affected.

Meanwhile, already facing competition from FinTech companies, and service digitalization, some banks will probably step up the process which will bring significant efficiency gains. In the environment created by the ordinance I expect to see larger banks do a better job navigating these stormy waters than smaller ones for whom survival looks trickier.

As far as private pension funds managing companies are concerned, they have just been handed an atomic time bomb. It lies in a section which received much less attention than it deserved and sets out that the amount of capital must be 10% of the value of contributions paid into the fund being managed.

This is a bombshell-provision as it will make or break the future of Pillar II. The threat this time is not that it will be explicitly dismantled, but implicitly ended by amending the business conditions to such an extent that shareholders might decide that it makes more business sense to leave Romania, even if they have yet to recoup their initial investments.

The situation was caused by the new capital requirements for pension funds which, besides being absurd, are very hard to grasp, economically. Whereas all the other tax measures set out in the ordinance are meant to increase budget revenues, the excessive capital requirements for pension funds managing companies have no such substantiation. And it is neither clear what other substantiation there may be.

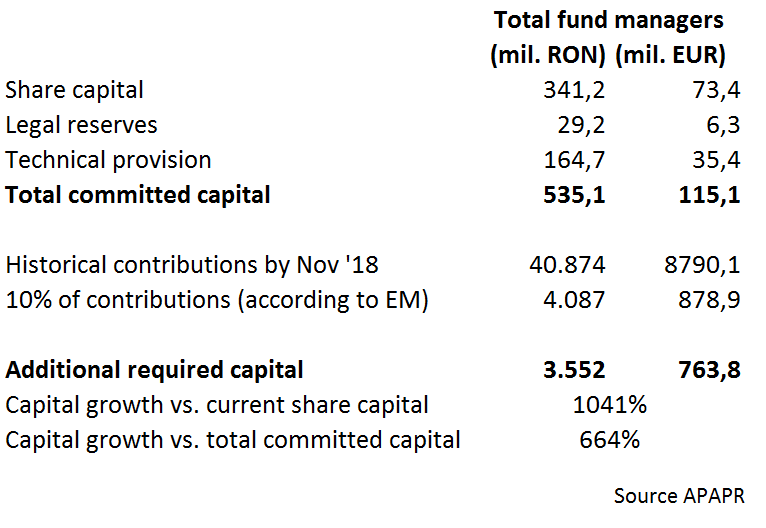

To better understand the issue, I am including below a table with indicative data based on the financial statements reported by Pillar II pension funds managing companies at the end of 2017.

The source of data is APAPR (Romania’s Private Pensions Funds Association), and the table lists both share capital and reserves, as well as provisions set up under the contribution guarantee law which is ultimately, also tied-up capital. As you can see, by arbitrarily setting a level of capital equal to 10% of historic contributions, you end up in a situation where private pension funds managing companies should contribute a further EUR 760 million, that is 10 times more than the existing share capital. I think that is unprecedented in any industry in Romania.

The source of data is APAPR (Romania’s Private Pensions Funds Association), and the table lists both share capital and reserves, as well as provisions set up under the contribution guarantee law which is ultimately, also tied-up capital. As you can see, by arbitrarily setting a level of capital equal to 10% of historic contributions, you end up in a situation where private pension funds managing companies should contribute a further EUR 760 million, that is 10 times more than the existing share capital. I think that is unprecedented in any industry in Romania.

To get a better perspective, according to APAPR data, since they arrived in Romania 10 years ago, fund managing companies made cumulative profits of less than EUR 400 million, and now they have to increase the capital by almost 800 million.

A key indicator when deciding to invest in a country is the return on equity (ROE) which is set against the risk of investing in that particular country. Under the circumstances created by the EM, the ROE for shareholders investing in Romanian private pensions will plummet. On the one hand due to a tenfold increase in the amount of capital set by law, and on the other, on account on lower profitability due to lower fees.

Let me be clear on this. The amendment is so radical, that many pension funds shareholders are likely to seriously ask themselves whether their presence in Romania is any longer justified. This will lead to the situation, certainly not desired by policy-makers, where the Romanian mandatory private pension system could be impacted by a lack of willingness on the part of pension funds managers to continue doing business that doesn`t make sense.

During his 1965 campaign for Governor of California, Ronald Reagan made one of his unforgetful remarks: “Government is like a baby. An alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no responsibility at the other”.

Have a nice weekend and Happy Holidays!

Subscribe to receive notifications when new articles are published