The prosperity of a country cannot be reflected by a single indicator

For many people, macroeconomic indicators are big unknowns. Concepts like the current account deficit or core inflation are not understood by most of the general public, or even by those in business, who prefer to ignore them. But this is not where the danger lies. After all, being aware of your own limitations keeps you safe from mistakes made under the illusion of all-knowingness. Such mistakes we encounter everywhere today, as the social media has created entire cohorts of “specialists”.

But not all economic parameters are free from the risk of over-valuation. Perhaps the most representative example in this category is GDP (gross domestic product) and its derivative, GDP per capita (gross domestic product divided by the number of inhabitants of a country).

But not all economic parameters are free from the risk of over-valuation. Perhaps the most representative example in this category is GDP (gross domestic product) and its derivative, GDP per capita (gross domestic product divided by the number of inhabitants of a country).

A search on the internet or in economics textbooks will tell you that GDP is the market value of all end goods and services produced in a country in a given period of time. The illusion of expressing the entire economy and development – some say prosperity – of a country in a single figure is what makes it extremely popular and overly used in most world hierarchies, ignoring the limitations and distortions it brings.

The same considerations apply to GDP/capita, another extremely popular indicator for world rankings, which this time is seen as a tool for measuring the quality of life in each country. It is usually adjusted to purchasing power parity, in order to increase comparability between individuals in different countries with different wages and different prices of goods and services.

Overuse of both parameters suffers basically from the same “disease”, namely “putting the cart before the horse”. I think we can start from the reasonable premise that the objective of any political leader, the promise they make when asking for the popular vote, is the welfare and happiness of the largest possible segment of the population. From this perspective, I must stress that, for many reasons, GDP/capita growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Unfortunately, however, there are many outspoken people who, out of convenience or political interest, absolutize this indicator, suggesting that a higher GDP/capita will necessarily improve the standard of living and satisfaction of most of the population. Which is false.

Ranking countries by GDP/capita paints an inconclusive picture

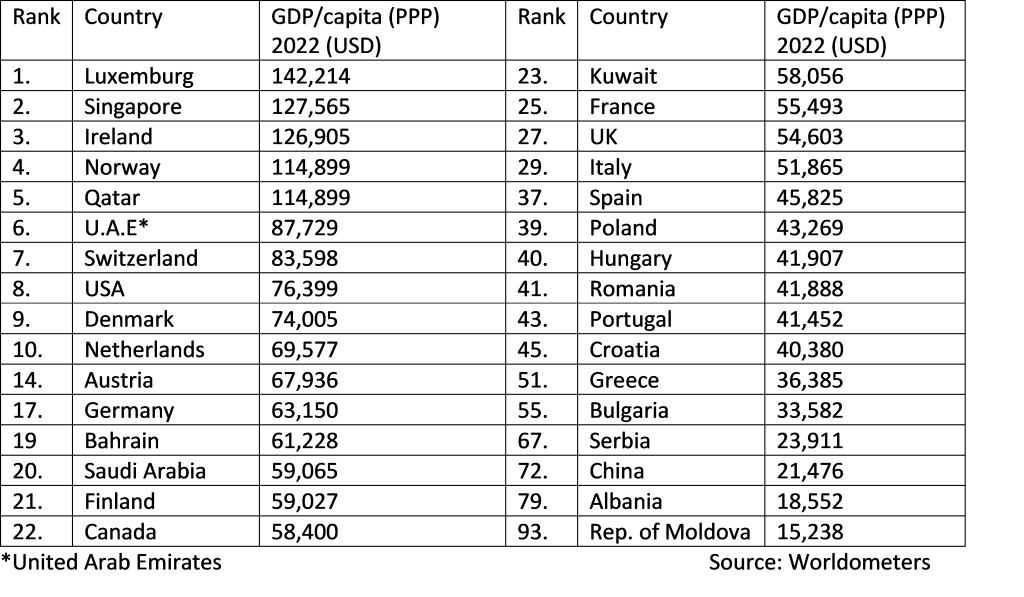

Illustrative is the table below, which shows a selective ranking of the world’s countries ordered by GDP/capita adjusted to purchasing power parity in 2022.

It is a table that captures very well the fact that a ranking by GDP/capita ends up producing a heteroclite, at times inaccurate, list of economic development patterns and the way in which the goal of a generalised and balanced welfare of the population is achieved.

This list suggests from the very first names the inadvertencies that such a parameter can bring. Luxembourg is in first place mainly due to the large number of expats working in this small country, producing added value, but not registered in the local population statistics.

On the other hand, as explained in an article on Politico, Ireland’s GDP per capita is distorted by the presence of over 1,500 multinationals that have registered in the country just to take advantage of low taxes. For instance, an unprecedented 26% growth in Ireland’s GDP in 2015 coincided with Apple moving its intellectual property assets to an Irish domicile. An adjustment for the presence of multinationals made by local statisticians reduces Ireland’s GDP by 40%.

The list is further completed by a mix of resource-rich and highly industrialised countries that essentially derive their wealth from two different sources: mineral resources or technology. This is an essential differentiation sustainability and competitiveness wise, which GDP per capita does not make.

GDP/capita does not reflect the quality of life in Romania for at least three reasons

As far as Romania is concerned, its position in this ranking compared to other countries in the region explains the triumphalist assessments that have dominated the public space in recent months. As can be seen, Romania is equal to Hungary, slightly below Poland and above Portugal, Croatia and Greece. But can we infer from this that Romania is as developed as Poland or Hungary, and superior to Portugal or Croatia? Or that Romanians have a higher quality of life than the Portuguese and the Croatians? As I said, one indicator is far from capturing the whole economic truth.

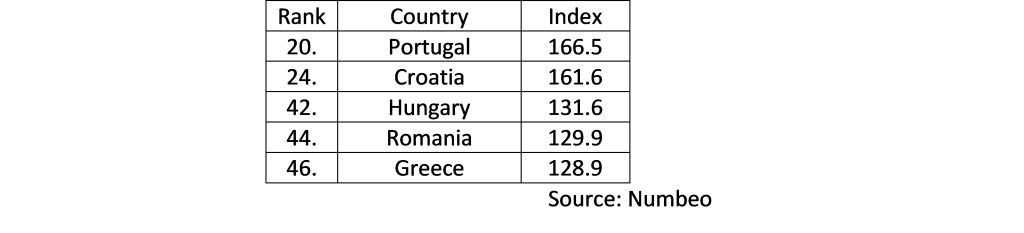

In fact, the Numbeo quality of life index shows a completely different picture by also using other criteria, such as safety, health, housing prices, pollution, climate, or commuting time. From the perspective of the quality of life index, Romania is below all these countries to which we proudly compare today for the fact that we have surpassed or equaled them in terms of GDP/capita, with Greece being the only exception.

The explanation lies in the fact that there are at least three major weaknesses of this indicator, GDP/capita, which ultimately paints a false picture. First, GDP per capita does not capture geographical economic polarization. In other words, it does not capture, for instance, the difference in development between Bucharest-Ilfov and Northern Moldova. While the former is at over 160% of the EU GDP/capita, the latter region is at only 46%. Croatia or Portugal, small countries with a greater homogeneity of development, have a GDP/capita at around 65-70% of the EU average.

The second distortion stems from the fact that GDP/capita distributes the economic results evenly over all Romanians without making any differentiation. Such an approach ignores the much larger discrepancies that exist in Romania between urban and rural populations. A rural area as underdeveloped as the one in Romania cannot be found in any of the countries with which we try to compare ourselves. Like any average, GDP/capita says nothing about how extreme the values from which it was calculated are, ignoring in the case of Romania the significant social polarization reflected by a Gini coefficient superior to all the countries to which we want to compare ourselves. But the wrong signals from GDP/capita don’t stop there.

For the development of a country, for the well-being of the population, the development of infrastructure is essential. And here I mean infrastructure in its broadest sense: transport, healthcare, education. But its development, especially in a country that has a lot of catching up to do like Romania, cannot be done without a state-run development plan. But for this to happen, it is not enough to have the will or the competence. Funds are also needed, a budget is needed to support the development of these types of infrastructure.

By looking too much at Romania’s GDP/capita and equating it with the welfare of the population, we overlook the fact that budget expenditure is not paid for out of the GDP, but out of budget revenues. In this respect, Romania is an exception in Europe, having by far the smallest budget in relation to GDP, and therefore the lowest public financial resources.

In other words, it is useless to have a GDP/capita similar or higher than other countries, if we do not use it to have better roads, hospitals and schools. Besides, the difference between the quality of infrastructure in Romania and countries like Croatia, Portugal or Hungary is visible to the naked eye when you visit them.

Neither GDP nor GDP/capita are able to capture an essential element that ultimately makes the difference between the well-being of the populations of different countries: the way wealth is distributed for the wider benefit of society. And that requires a strong middle class, distributed across the country, and public funding of sustained and balanced infrastructure development. Otherwise, behind the rosy economic indicators there will be two terribly different Romanias: one in Europe and the other outside it.

Subscribe to receive notifications when new articles are published