2024 was a truly special year. Around the world, more than 80 national elections were held, involving 4.2 billion people – over 50% of the world’s population. Foreign Affairs magazine estimates that an electoral cycle of this magnitude will not occur again until 2048. Against this backdrop, it is somewhat ironic that the subject we propose to address is precisely the regression of democracy worldwide.

Unfortunately, this is exactly the trend suggested by prestigious institutes such as Freedom House, V-Dem or the Economist Intelligence Unit. Assessments are not easy, as a country’s level of democracy cannot be judged in black and white and developments of this kind are not usually sudden.

The V-Dem Institute is an independent research institute that operates alongside the Department of Political Sciences of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. It is famous, among other things, for the annual report it produces, analyzing the evolution of democratic standards in over 170 countries according to multiple criteria.

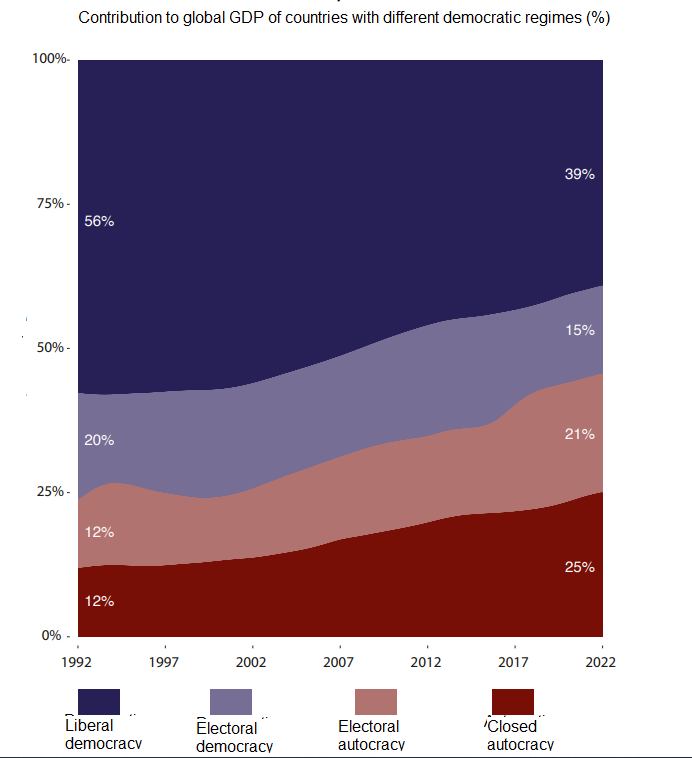

The analysis is carried out by dividing the political models of the countries analyzed into four categories

a) closed autocracies (democratic principles are not respected),

b) electoral autocracies (democratic principles are imitated and/or fulfilled to a limited extent)

c) electoral democracies (democratic principles are partially fulfilled)

d) liberal democracies (all democratic principles are fulfilled)

The approach based on this model has produced the graph below, which describes democratic regression around the world in recent decades.

Considering that the values are weighted by GDP, at first sight, such a trend could be attributed primarily to the spectacular economic development of China, a country rather among closed autocracies. However, it must be acknowledged that weighting by GDP makes sense, given that with economic power comes the temptation to seek out and create allies with similar democratic standards. In other words, non-democratic regimes will more easily find political and economic support among the large countries and economies that share their values. Just as the great democracies have promoted these norms around the world through soft power, the great autocracies promote their values through the economic power at their disposal. According to V-Dem, over the last 30 years, the economic dependence of democratic countries on autocratic ones has doubled.

The bad news is that, even adjusting for the impact of major economies such as China and the USA, the world’s democratic evolution does not look much different, as a recent analysis published by professor and former dean of the INSEAD University, Ilian Mihov, concludes.

The irony is that, in most of the countries that have significantly lowered their democratic standards, the political power that initiated these trends was democratically elected. In a recent analysis, Foreign Affairs magazine reports that out of the 30 countries that lost their democracy from 2006 onwards, in 27 of them autocracies were brought to power by democratic vote. The trend is all the more worrying as it does not only concern emerging countries, where the check and balances system is fragile and easy to eliminate or imitate. Developed countries, too, seem to move towards leaders who flirt with or are avowed admirers of established autocrats.

How did this come about? Are Westerners less attracted by the power of the vote? Does it still matter to them if they will live under an autocratic regime, putting their future at the mercy of a more or less enlightened despot?

That would be the simplistic way of looking at things. In reality, the explanation is more complex. Because it is not their autocratic sympathies that make right-wing and far-right leaders popular among the electorate, but a number of topics from their political agenda that are considered far more important.

In a text published in 2016, “The war of the century which will define our future”, I explained that globalization has led to a rapid increase in the imbalance between the two main factors of production, capital and labor. In developed countries, capital holders, an extremely mobile and relatively rare resource, have been the big winners. On the other hand, the owners of “labour” in these countries have been the big losers, given the huge resources of “labour” offered to “capital” by emerging countries.

Under these conditions, I explained that those who offer “work” have only the vote at their disposal, that instrument which does not take into account how much money you have in your account and which offers people the unique opportunity to sanction the economic and political elites. And yes, precisely economic nationalism, the use of national capital for the development of one’s own country and protectionist policies are part of right-wing leaders’ agendas.

But the turn to the right in the Western world was also a defensive reaction of a large segment of the population, to the slide of the main stream parties towards the far left. They made political correctness a religion, justifying majority discrimination in favor of minorities, relegating meritocracy to the background and leading to a shocking reappraisal of universal history. For many, precisely these approaches already represented forms of limiting democratic expression, free thinking, overshadowing the risks of right-wing leaders with authoritarian tendencies coming to power.

But the series of errors did not stop there. The approach to the green transition, the measures aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions, has been disastrous. This is probably a case study that could be used in MBA programs to explain to students how change management should not be done. The methods associated with administering such a process start from a simple, well-known truth: people don’t like change. Mainly when they affect them directly, they are sudden, far-reaching and create an unpredictable situation. This aversion has no chance of diminishing when communication is unable to coherently explain what the costs of achieving the objective are and why they are worth bearing. Aversion has no chance of diminishing when changes, instead of being gradual in intensity, start with the toughest measures.

Not to mention the tensions brought to the energy market by the inaccurate assessment of the gap between supply and demand, which led to the closure of nuclear power plants (in Germany) based on purely ideological criteria, only to open up new coal-fired ones to re-balance the system. In the end, ambitious and poorly prepared targets have led to economic costs for both the industry and the population, accompanied by loss of competitiveness and social tensions.

Last but not least, a mixture of ideological leftism, naivety and economic interests meant that an overly permissive immigration policy led to a reaction of rejection on the part of the population. Mirroring in another form the “war” between capital and labor, the economic and political elites cooperated to maintain an excess of supply on the labor market in order to keep labor costs low. It is worth noting the shift in doctrine of the political left, which has gone from being the traditional advocate of “labour” to an advocate of immigration flows. The downplaying of the economic and social consequences of immigration by the mainstream parties led to the reorientation of an important segment of the population towards the right-wing parties, which promised to put an end to the exodus of immigrants.

But beyond the fact that right-wing leaders are wanted for their nationalist and conservative agenda, can we really ignore their autocratic temptations or sympathies? Can voters really be reassured that Western democratic systems contain sufficient regulatory mechanisms to prevent the establishment of an electoral autocracy?

Well-known Financial Times chief analyst Martin Wolf, speaking about the US, makes a valid general point that should not be ignored at all. “Law-governed, liberal republics are always fragile. They are not so much protected by institutions, as by the values and courage of the people who run those institutions and of those who hold positions of influence in society. This includes those in business. It is natural to believe that the games of business or politics are safe. But both depend on the institutions of the state. It is naive to expect that they will survive all attacks.”

And to confirm these assertions, we don’t have to go very far. Just look at the political developments of recent years in a number of former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, nota bene, all EU members. They have provided the hard proof that, yes, state institutions can be perverted, they can be controlled in such a way that, while they appear at first glance to comply with the standards of separation of powers, they are in fact aimed at weakening democratic standards and putting state institutions at the service of a person and the political and economic elite that surrounds him.

Larry Diamond, professor at Stanford University, referring to the concept of “the fallacy of electoralism”, draws attention to the fact that “democratic election is only the beginning.” “Without honest and effective governance, a capable state, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and a vigilant civil society, democracy will not deliver the economic growth, physical infrastructure, social services, public health, human rights, and safety and security that its voters expect.”

What should give us pause for thought is the fact that the slippages in Central and Eastern Europe have occurred in the context of still solid democratic regimes in Western Europe and the USA. But what will happen when these countries are governed by leaders with autocratic tendencies? In what direction will things evolve in the geographical region where Romania is also located, in the absence of the reference system by which they have been measured up to now?

I will not forget the image of the American government meeting attended by one of the recent presidents, which, for those old enough, would have been a déjà vu, reminiscent of Communist government meetings in the humility of the interventions and the praise addressed to the Leader. After all, the cult of personality is possible everywhere, from Asia to North America, provided the leader has an ego big enough to surround himself only with flatterers and yes-men. The essential problem is that critical decisions will remain at the discretion of a single person who, isn’t it, can never be wrong, whatever economics of political science may say.

In conclusion, the risk does not come from the shifting electoral agenda of Western voters trying to pour in trends with which large segments of the population disagree. The problem lies in the fact that, as long as mainstream parties continue to ignore the priorities of the electorate, votes will flow to right-wing leaders, despite their populism and sympathies for autocracy. The major risk is that the latter will believe they are also preferred for their autocratic temptations and feel encouraged to move in that direction. There is only one solution and it requires a healthy dose of humility: the mainstream parties learn from their mistakes and reconnect to the electorate’s real agenda. Simply invoking the danger of autocracy is clearly insufficient.

Subscribe to receive notifications when new articles are published